Introduction

Peatlands, characterized by the accumulation of organic matter in waterlogged environments, play a crucial role in maintaining global biodiversity and Carbon storage. These unique ecosystems provide habitat for a variety of plant and animal species, including birds. However, peatlands around the world have been extensively degraded due to drainage, agriculture, and other human activities. The restoration of peatlands has emerged as a vital land-based emissions reduction strategy[1], and is being widely undertaken in Wales. But what will the effect of this restoration be on the bird community and populations in Wales? And how does this balance against the likely effects of climate change on the birds of Wales?

Peatland in Wales

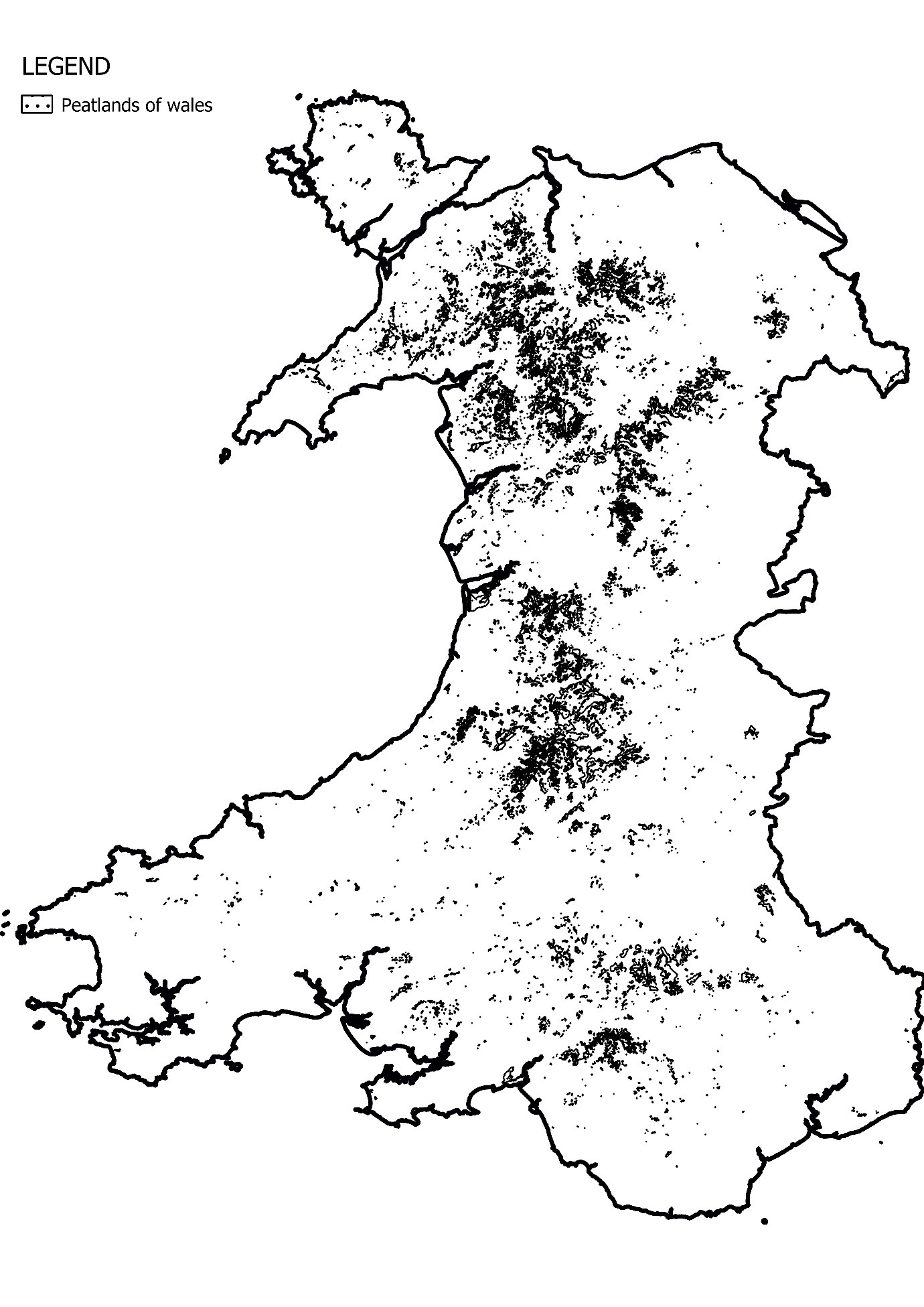

Wales supports approximately 120,000 ha of peaty soils, a large proportion of which are in unfavourable condition[2]. This includes areas of lowland fen and raised bog such as Cors Caron and Cors Ffochno. Although much is made up of upland blanket bog draped over the spine of Wales. This is found in the counties of Gwynedd, Ceredigion and Powys and extends as far south as the Brecon Beacons and the upland areas of Glamorgan (Figure 1).

The recent recognition of the importance of peatlands for emissions reduction has resulted in Welsh Government policy change. Welsh Government’s long term Peatland Policy (Welsh Government Ministers Decision Report 26, June 2019) is ambitious and focusses on (i) ensuring “all peatlands with semi-natural vegetation are subject to favourable management/restoration (a minimum estimated area of 30,000 ha)”, and (ii) restoring “a minimum of 25% (~c. 5,000 ha) of the most modified areas of peatland”.

It is currently estimated that ~18,000 ha of deep peat in Wales is afforested of which ~11,000 ha is owned by Welsh Government (WG). Thus, peatland restoration in Wales has two distinct elements; the restoration of open peatland and, forest to bog peatland restoration, with forest to bog restoration on the WG woodland estate offering a significant opportunity for quick delivery[3].

Figure 1 - Peatlands of Wales. This map shows areas where soils are likely to consist of >40cm depth of peat.

Peatland Birds in Wales

Many species breeding in Welsh peatlands are recognised as internationally important with designations and legal protection granted to them. Blanket bogs, lowland raised bogs and fens all hold distinct bird assemblages. However, it is the breeding bird assemblage of UK blanket bogs that is outstanding. Within blanket bogs, the wettest habitats (open pools and un-drained bog) are often utilised by wildfowl and dunlin Calidris alpina, whilst areas of tall vegetation (often in mosaics with upland heathland) provide cover and nesting sites for black grouse Lyrurus tetrix, curlew Numenius arquata, hen harrier Circus cyaneus and merlin Falco columbarius[4]. Golden plover Pluvialis apricaria, redshank Tringa totanus and skylark Alauda arvensis are also often present associated with shorter vegetation[5]. The small numbers of Welsh breeding dunlin (Figure 2 & 3) are now largely confined to peats and wet heath in our best quality upland blanket bog.

Climate Change and Birds

The effects of climate change on birds in Wales will likely be mixed[6]. Many common and widespread resident birds will be helped through a reduced risk of cold weather mortality in winter, but our unique assemblage of upland bird species, which include those associated with peatlands, are likely to be major climate change losers. This includes species such as golden plover and dunlin, for whom hot dry summers will reduce the abundance of key invertebrate prey (e.g. tipulids), impacting breeding success and population trajectories of these species[7].

Golden plover (Figure 4 & 5) and dunlin have both undergone dramatic declines as breeding birds in Wales, with at least a ~40% drop in the numbers of breeding dunlin since 1975 and an 88% drop in breeding golden plover numbers[8]. Both species were traditionally associated with the upland spine areas of Wales and the general increase in Molina caerula dominance (possibly as a result of peatland degradation) has been implicated in their decline.

Figure 2 – Dunlin (Calidiris alpina). Photograph by Paul Roberts.

Figure 3 – Dunlin (Calidiris alpina). Photograph by Paul Roberts.

Figure 4 – Golden Plover on nest. Photo Colin Richards.

Figure 5 – Golden Plover eggs in nest. Photo Colin Richards.

Peatland Habitat Restoration

Peatland restoration primarily involves techniques to bring the water table closer to the surface and ‘rewet’ previously drained areas. This is often achieved through drain or grip blocking in open habitats, alongside supporting actions such as planting important peat-forming sphagnum . Forest to bog restoration is, however, more intrusive due to the higher density drainage network installed in this habitat. Forest to bog restoration usually involves large scale mechanical interventions using earth moving machinery to remove or flip tree stumps, smoothing the ground surface and removing the drainage network (see example here - https://youtu.be/h-nPehdDQsk).

Peatland Restoration and Conservation of Threatened Species

Increasing the water table in open peatlands changes the vegetation structure, which in turn alters the invertebrate community and subsequently the bird assemblage. This may support the conservation of threatened bird species through increasing invertebrate prey abundance[9]. For example, research has shown that soil moisture levels can be key for tipulid numbers[10]. Restoration may also increase general habitat suitability through a reduction in Molinia dominance and move towards a more varied bog vegetation community[11] [12].Indeed restoration in northern England has been shown to have positive population effects on golden plover, dunlin, curlew, skylark and dipper Cinclus cinclus with negative effects on meadow pipit Anthus pratensis[13] [14].

Widespread peatland restoration in Wales may help our struggling upland breeding bird assemblage, but to date there is little evidence of this, with studies from other countries largely ambiguous in their results[15].

The lack of evidence is even more obvious when you consider the potential effects of forest to bog peatland restoration, with a lack of published data on birds to date (Current research by R. Hughes at RSPB Forsinard will help address this). Despite this lack of evidence it is probably reasonable to surmise that the landscape change from forest to open habitat will support open habitat specialist species present (e.g. Dunlin, curlew etc) through the removal of refuges for ground-based predators and vantage points for avian predators (both known negative effects of plantation woodland in the uplands [16][17]).

Forest to bog habitat change is also much more dramatic than open habitat restoration, involving a loss of plantation woodland and the associated bird community followed by conversion to a more open habitat and community. We also know that plantations can support species of conservation concern, with young plantations often being key for breeding redpoll Acanthis sp, common crossbill Loxia curvirostra and tree pipit Anthus trivialis [18], whilst mature plantations can be key for nesting goshawk Accipiter gentilis. It would also seem likely that forest to bog restoration will lead to a net loss in the number of birds present and species diversity, but this must be weighed against the opportunity it will provide for more specialist upland species.

There is a clear need for further research here!

Carbon Sequestration and Climate Change Mitigation

Peatlands are vital carbon sinks, storing vast amounts of carbon in their organic soils. Restoring degraded peatlands can help mitigate climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions[19]. The conservation and restoration of peatlands prevent the release of stored carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. These efforts contribute to the conservation of bird species indirectly by preserving their habitat and maintaining suitable climatic conditions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is limited published evidence of peatland restoration initiatives having positive effects on bird species to date from the U.K. There is also a general lack of evidence on the effects of open peatland habitat restoration and particularly forest to bog restoration on bird species and communities. However, there is evidence to support likely positive effects of restoration through effects on habitat quality and food biomass abundance for some upland breeding bird specialists.

There is also good evidence of the likely negative effects of climate change and plantation woodland on our upland breeding bird assemblage. As such, works to aid the recovery of degraded peatlands is likely to benefit some birds whilst also contributing to climate change mitigation and the overall health of ecosystems and should be a net benefit for the birds of Wales. There is however a need for more detailed research in this area and detailed to monitoring of restoration completed to date to provide a robust evidence base for future restoration.

[1] https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/land-use-policies-for-a-net-zero-uk/

[2] Vanguelova, E., Broadmeadow,S., Anderson, R., Yamulki, S.,Randle, T., Nisbet, T. and Morison, J. (2012). A Strategic Assessment of Afforested Peat Resources in Wales and the biodiversity, GHG flux and hydrological implications of various management approaches for targeting peatland restoration. Report by Forest Research staff for Forestry Commission Wales Project, with Reference No 480.CY.00075 (T), October 2012

[3] https://cieem.net/afforested-peatland-restoration-in-wales-by-mike-shewring/

[4] Pearce-Higgins, J.W., Grant, M.C., Beale, C.M., Buchanan, G.M. & Sim, I.M.W. (2009a) International importance and drivers of change of upland bird populations. Drivers of Environmental Change in Uplands (eds A. Bonn, T. Allott, K. Hubacek & J. Stewart). Routledge, Abingdon, UK, pp. 209-227

[5] Pearce-Higgins, J.W., Grant, M.C., Beale, C.M., Buchanan, G.M. & Sim, I.M.W. (2009a) International importance and drivers of change of upland bird populations. Drivers of Environmental Change in Uplands (eds A. Bonn, T. Allott, K. Hubacek & J. Stewart). Routledge, Abingdon, UK, pp. 209-227

[6] https://www.bto.org/sites/default/files/publications/bto_climate_change_and_uk_birds_-_james_pearce-higgins_bto_web-compressed.pdf

[7] Carroll, M. J., Dennis, P., Pearce‐Higgins, J. W., & Thomas, C. D. (2011). Maintaining northern peatland ecosystems in a changing climate: effects of soil moisture, drainage and drain blocking on craneflies. Global Change Biology, 17(9), 2991-3001.

[8] Pritchard, R., Hughes, J., Spence, I.M., Haycock, B. & Brenchley, A. (Editors). (2021). The Birds of Wales Adar Cymru. Liverpool University Press.

[9] Andersen, R., Farrell, C., Graf, M., Muller, F., Calvar, E., Frankard, P., Caporn, S. and Anderson, P., 2017. An overview of the progress and challenges of peatland restoration in Western Europe. Restoration Ecology, 25(2), pp.271-282.

[10] Carroll, M. J., Dennis, P., PEARCE‐HIGGINS, J. W., & Thomas, C. D. (2011). Maintaining northern peatland ecosystems in a changing climate: effects of soil moisture, drainage and drain blocking on craneflies. Global Change Biology, 17(9), 2991-3001.

[11] Hancock, M. H., Klein, D., Andersen, R., & Cowie, N. R. (2018). Vegetation response to restoration management of a blanket bog damaged by drainage and afforestation. Applied Vegetation Science, 21(2), 167-178.

[12] Bellamy, P. E., Stephen, L., Maclean, I. S., & Grant, M. C. (2012). Response of blanket bog vegetation to drain‐blocking. Applied Vegetation Science, 15(1), 129-135.

[13] Wilkinson, NI and Douglas, DJT (2015) United Utilities Sustainable Catchment Management Programme (SCaMP): monitoring the response in bird abundance, 2005-2014. Report to United Utilities.

[14] https://www.iucn-uk-peatlandprogramme.org/sites/default/files/2019-11/COIMON~1.PDF

[15] Alsila, T., Elo, M., Hakkari, T., & Kotiaho, J. S. (2021). Effects of habitat restoration on peatland bird communities. Restoration ecology, 29(1), e13304.

[16] Wilson, J.D., Anderson, R., Bailey, S., Chetcuti, J., Cowie, N.R., Hancock, M.H., Quine, C.P., Russell, N., Stephen, L. and Thompson, D.B., 2014. Modelling edge effects of mature forest plantations on peatland waders informs landscape‐scale conservation. Journal of Applied Ecology, 51(1), pp.204-213.

[17] Hancock, M.H., Klein, D. and Cowie, N.R., 2020. Guild‐level responses by mammalian predators to afforestation and subsequent restoration in a formerly treeless peatland landscape. Restoration Ecology, 28(5), pp.1113-1123.

[18] Burgess, M.D., Bellamy, P.E., Gillings, S., Noble, D.G., Grice, P.V. and Conway, G.J., 2015. The impact of changing habitat availability on population trends of woodland birds associated with early successional plantation woodland. Bird Study, 62(1), pp.39-55.

[19] Lees, K.J., Quaife, T., Artz, R.R.E., Khomik, M., Sottocornola, M., Kiely, G., Hambley, G., Hill, T., Saunders, M., Cowie, N.R. and Ritson, J., 2019. A model of gross primary productivity based on satellite data suggests formerly afforested peatlands undergoing restoration regain full photosynthesis capacity after five to ten years. Journal of environmental management, 246, pp.594-604.